Last week I wrote about the new project we are starting this year in Antarctica. We will study the changes that happen to the ecosystem as glaciers retreat. Let's talk a bit more in detail about what that means. (Warning! I'm going to use words that I introduced in my last post. It's time to test your vocabulary!)

A big part of the changes that happen during ecological succession is from the interactions between plants and soil. What do I mean by that? When plants arrive on bare soil, they change the soil. They can add nutrients, protect the soil from the wind and cold temperatures, and eventually become food for other organisms. These changes in the soil help the microscopic organisms (or "microorganisms") living there. If plants add food and nutrients to soil and protect from the weather, it becomes a better habitat for soil microorganisms. When plants start to grow, more organisms can move into the soil!

Those soil microorganisms are very busy! They help recycle nutrients and eat dead plant material. That makes the soil more fertile for plants. So now even MORE plants can move in, which creates even MORE food for organisms, so MORE organisms can live there... It's a cycle of back-and-forth interactions between the soil and plants! We call this "plant-soil feedbacks".

On the Antarctic Peninsula, one of the hardy plants that moves in first is moss. Moss are very tough plants! They can survive for a long time, even if they are frozen, completely dry, or in the dark. They become dormant, and wake back up when the weather improves. That's an important skill when you live in Antarctica! Moss can also get their nutrients from both the air and soil, which helps them survive without as much help from the soil.

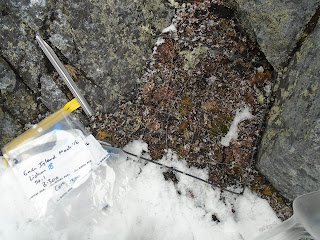

Another early grower is lichen. Lichens are a unique kind of organism. They are a plant and fungus living together in one organism! They are VERY good at surviving in tough habitats. They are so good at surviving on their own that they don't even need soil. They can grow right on rocks!

|

| The green stuff on the rocks and the tufts on the soil are both examples of lichen. |

Moss and lichens are often the first to arrive on new soil. We call them pioneer plants. Just like the pioneers from your history books, they can move into new territory and survive through hard times! But not all species of moss and lichen are good pioneers. Only some species can start growing on the bare soil. Their growth starts the plant-soil feedbacks, and paves the way for other species of moss and lichen to move in.

Eventually, the soil becomes fertile enough for grass to grow. There is only ONE species of grass on the entire continent of Antarctica. It is called Antarctic hairgrass. (Compare that to the thousands of species of grass that live in the United States!) Grass is a "vascular" plant. That means it has veins that move water through the plant, allowing them to grow taller (and farther away from water) than moss and lichen. The only other vascular plant in all of Antarctica is the Antarctic pearlwort.

|

| Pearlwort in the center surrounded by hairgrass |

As succession continues and these vascular plants move in, the community can look like this:

|

| Look that that diversity! Many species of lichens, growing on moss, with grass and pearlwort (that patch of bright green in the lower center), and even mushrooms! |

Fun fact: Hairgrass and pearlwort can only grow on the Peninsula, because the rest of the continent is too harsh. They are the wimpiest of the Antarctic plants. :) Moss and lichen are able to grow in many places in Antarctica, but hairgrass and pearlwort can only follow them on the Peninsula.

So these are the species that we will be studying during our research. Mostly, we will focus on the moss, lichens, and hairgrass.